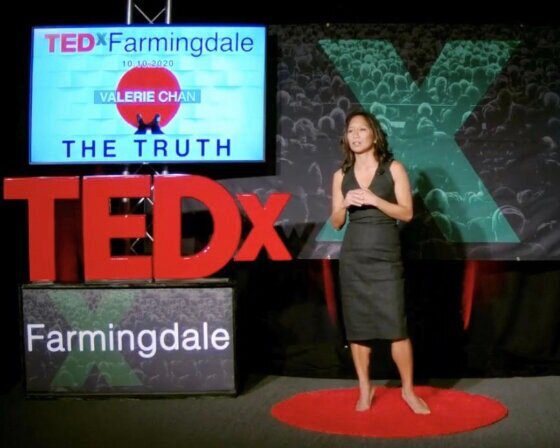

On October 10, Plat4orm’s Principal Valerie Chan presented at TEDxFarmingdale on “Reawakening the Senses During COVID”. The following is part two of a two-part post detailing her experience preparing to give a TEDx Talk.

In Part 1 of my story, I described the process I went through to develop an idea appropriate for a TEDx talk, get it accepted and do the research and writing. In this post, I discuss the preparation for the actual delivery of my talk.

MEMORIZATION

First, a confession: While I have made presentations on PR, marketing, crisis communications and many other types of related content, and I have talked at dozens of venues before—including the NASDAQ Entrepreneurial Center, Hastings Law School, as well as ILTACON and other conferences—I had never written out word-for-word nor memorized a 12- to 14-minute talk. Before presenting at TEDx, I’d always hidden behind slides and presentation notes.

In my TEDx talk, however, I researched and wrote the entire talk, weaving in my personal story because I knew I had to embody the talk in a way that didn’t depend on the rote memorization skills I learned playing the viola growing up.

Just like I did during the two years I spent re-patterning my brain (and body) to help myself recover from a serious brain accident—I seriously trained to deliver this TEDx talk. Every day for over a month, first thing in the morning, I would wake up and listen to the audio file so that it would enter my brain and stay there.

As I listened, I would visualize myself on-stage talking and giving my speech. I would then rehearse the talk at least twice afterwards, performing these series of exercise diligently and sometimes working two or three hours a day to ensure that I had fully memorized the talk to the extent that I no longer had to think about it—it was simply a part of me.

One reason we memorize each detail of a talk is because our nerves take over when we are on stage. In fact, even after all my preparations, during my live talk I forgot an entire paragraph. Unfortunately, because of a mic glitch, after about two minutes in to giving my talk, I had to start over again when they discovered my mic was off.

And then my nerves took over. After a series of deep breaths and what seemed like 10 minutes, I walked in front of the glaring lights and eight cameras and began again.

Because my nerves were shaken, I blanked out to what I was going to say—about five paragraphs in. At that point, I started from where I remembered—and this was only after taking three breaths and remembering why I was sharing my message. It was only about a third into the talk when I began to get my groove back, able to improvise where I knew I needed to, and emphasize the key points. It was at that point my passion took over and the words came out of me—and that was thanks to memorization.

EMBODIMENT OF THE TALK

Let’s be clear, memorization is not the same thing as embodiment.

While it’s one thing to memorize a paragraph, a page or an entire speech, to really communicate the meaning behind the words you need to live, breath and feel what you’re saying, and you need to do that every day until you give the talk.

Because my TEDx talk was my story, it was easier to tell. I lived it every day for several years—and am still living with some effects of my accident—but even so, articulating and sharing my story is often difficult.

As an Asian American, I was taught by my family to compartmentalize. We don’t air dirty laundry, and we don’t talk about our weaknesses because that would be an admission of defeat. If we don’t feel we’re as good as a favorite cousin or sense our relatives may not be proud of us, it’s always because we’ve revealed a weakness.

To admit I had a brain injury—not just to the more than 800 people who watched the live stream or the 22+ million TED subscribers who may potentially see my video, but to potential prospects, my staff and my colleagues—isn’t something that feels comfortable for me. Given that I am in the legal field guiding marketers and attorneys to say certain things, or execute on specific strategies and tactics, admitting a weakness feels like I am saying, ”Hey, I may not actually have the credibility to help you succeed.”

In fact, the paragraph that I blanked out on during the live talk was about how I’m living with my brain injury now, seven years after the accident. To this day, I reverse words and numbers, even though my brain wants to say something else. I also still wince when a car goes into my lane on the freeway and I still slur my words if I’m tired.

But trying to talk about these difficult and very personal things was an essential component of the talk. To be effective, I needed to be able to embody the emotion behind my topic, to convey the feelings the topic stirs up in me so that people can get beyond intellectual understanding to something deeper. That meant that I couldn’t live in my head like most of us habitually do.

PRESENTATION

Because of COVID, the format of this TEDX talk was different. First, a live audience was non-existent due to indoor capacity restrictions. Second, imagine having eight cameras and hot lights glaring down at you. That’s what happened during my talk. Two cameras were used to live stream and the other six were used to get different angles to create a professionally produced video for the TED site. Speakers were asked to stand on one red circle for the cameras. We could move within that circle, but we couldn’t pace, and we had to act naturally—or as naturally as you possibly can with eight cameras and lights all pointed at you.

Honestly, the broadcast skills that we communications professionals teach our clients help people talk with an anchor, a producer, or a broadcaster, but they don’t train you to deliver a monologue in front of cameras and lights. When you are alone on stage or in front of a camera delivering a monologue, it’s just you. With keynotes, often there’s a “vanity camera” so you know what slide is in the background and/or sometimes there is a prompter so that you can remember lines. But with this TEDx experience, there was none of the prompting you normally would get if you were in a broadcast studio. Instead, it’s just you talking about your experience, reliving your experience and giving a message that you hope will inspire others.

During all the rehearsals, staying focused on the experience and the message was the one thing that kept me going. The memorization, because it was embedded in my brain, was important, but it was the embodiment that I practiced, actually feeling in my body what my talk was about and the passion that came out in the talk, that made my talk work—and that was true of all the best talks on stage. You must maintain a presence to be a compelling speaker, and unless you can fully relate to the subject that you are giving, you are not going to be an effective speaker.

Overall, I thoroughly enjoyed my experience with TEDx. While COVID changed a few things, from the topic of my speech to not speaking in front of a packed house, I walked away from the experience with a better appreciation of myself, my abilities and how to serve my clients better. It was truly a life-changing opportunity.

Valerie Chan is principal and founder of Plat4orm. Email her at valerie@plat4orm.com.